(My column in Mint Lounge, May 20 2017)

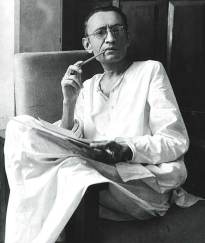

In his poignant Partition story Khol Do (1948), Saadat Hasan Manto presents a traumatically widowed father desperately seeking his missing daughter. He describes her features to a group of boys and prays for their success in finding her. They locate the girl, but the old man only sees his daughter many days later, on a hospital stretcher, having been retrieved from a railway track. The doctor in charge asks him to open the windows—khol do—but response to the command comes from the half-conscious girl. Instinctively, her hands undo the knot of her trousers, and she pushes them down to her thighs, spreading her legs. The father rejoices—the girl is alive. But the doctor breaks into a sweat. Partition wasn’t only about drawing boundaries.

It was with this story that Manto arrived in Pakistan, and for his pains he was promptly slapped with a lawsuit for obscenity. In the end, he had to pay Rs300 for the mirror he had held up, but this was, by 1950, a familiar exercise—he had already battled charges of vulgarity thrice before in colonial India and would face it once again in postcolonial Pakistan. As always, fuelled also by alcohol and cycles of depression, he remained defiant. “How,” he asked, “could I bare a culture, civilization and society that is already naked?” People could call him “black-penned, but I don’t write on the blackboard with black chalk; I use white chalk so that the blackness of the board becomes even more evident.” Understandably, the man upset many.

Manto was born in May 1912 and grew up in Amritsar. On the side of his father, a stiffly starched judge, he was descended from Kashmiri traders, while his mother, a neglected second wife, was Pathan. All his father’s sons from the first wife were samples of upper-class correctness, educated abroad to become barristers and engineers. Manto alone was an embarrassment, a “slacker, gambler, drinker…and inveterate prankster…an entirely unworthy son of an honourable and respected man”. He once roused Amritsar into a nationalistic frenzy by manufacturing a rumour that the British had sold the Taj Mahal to the Americans, but more scandalously he kept in his bedroom, alongside his father’s photograph, posters of Joan Crawford and Marlene Dietrich (whose legs he apparently admired).

Energetic, mischievous and headstrong, it took him three attempts to get through school (where he failed Urdu, the language that would deliver him to fame), while at university in Aligarh he barely lasted a year. But the dropout was sensitive, talented, and married his keen interest for the marginalized with unyielding scorn for hypocrisy. Part of this came from his family’s second-class treatment in his father’s home, and the rest from resenting discipline of any kind. Critics said he was influenced by Freud and Marx and Chekhov and Tolstoy, but as his biographer and grand-niece Ayesha Jalal writes, Manto himself viewed “his proclivity for storytelling as quite simply a product of the tensions generated by the clashing influences of a stern father and a gentle-hearted mother”.

“A man remains a man,” he once observed, “no matter how poor his conduct. A woman, even if she were to deviate for one instance from the role given to her by men, is branded a whore.” His was not sympathy as much as a genuine understanding of experiences common to women and the powerless. When lambasted for highlighting unvarnished characters from the peripheries of society, he asked: “If one could talk about temples and mosques, then why could one not talk about whorehouses from where many people went to temples and mosques?” There was greater sincerity, he felt, in the life of the prostitute than in that of a mahatma, and his stories were wedded to reality, eschewing romance and all idealism except that of humanity.

Manto began in the early 1930s as a film critic, quite by accident, and then became a translator. By 1934, he had published his story, Tamasha, and two years later, produced his first collection even as he left Amritsar for Lahore and, then, what was Bombay (Mumbai). By 1940, he was in Delhi, married to Safia, whose influence enriched his work, and whose parents gave him a roof, for he was still no richer in the pocket. He had a job with All India Radio, and it was now that Manto became a household name, producing in two years over a hundred plays to air. In his usual uncompromising style, he also managed to provoke many at his workplace, storming out eventually with his typewriter when they attempted to revise his works.

Between 1942-46, Manto lived in Bombay again, writing film scripts and making some money, afflicted, however, by a feeling of inadequacy. “I have started drinking a lot, not so that I can write… but actually to find something within me that I have to do.” Whatever he had achieved so far, he felt, was “a mere travesty”, but really it was powerful writing. “It is a rule in every respectable country…that the dead, even if one’s enemies, are spoken of in positive terms…. I damn such a respectable world and society where as a rule the character of the dead is sent to a laundry for a wash…. In my reformatory there is no support, no shampoo, no hair-curling machine…I am not a make-up artist…all the angels in my book have their heads shaved, and I have performed that ritual with great finesse.”

Partition for Manto was not about politics. “I think only of (raped women’s) bloated bellies—what will happen to those bellies?” Would the offspring “belong” to Pakistan or India? When he moved to Lahore, many in India felt betrayed. But Manto, despite the 127 stellar stories he would produce there, wasn’t particularly cheerful about his new passport either, lapsing again into alcoholism. The bottle killed him in 1955, and he left behind Safia and three daughters. Honour was heaped on him in death, but it was precisely the kind of honour he despised, warning in advance that he would take it as “a great insult” to be garlanded by a “fickle-minded” state. Yet garlands were what he received, for after all, as one critic wrote, he had left behind “pearls of truth”, albeit with the warning that if “we find the truth bitter, it is not Manto who is to blame”.