(My column in Mint Lounge, August 12 2017)

In 1877, at the height of the Great Famine that devastated the south, a distinguished Englishman, recently knighted for services rendered to the British empire, yet again took a vociferous stand against the policies of his queen’s government in India. For years he had railed against imperial overzeal for the railways—a sophisticated scam that funnelled out Indian resources while delivering unconscionable profits to faraway investors—and now he was vindicated. For “we have before our eyes,” he noted, “the sad and humiliating scene of magnificent (rail) Works that have cost poor India 160 millions, which are so utterly worthless in the respect of the first want of India, that millions are dying by the side of them.” The railways certainly brought grain to starving masses, but the costs were so disproportionately high that nobody could afford to buy them—official profiteering perverted even the delivery of famine relief.

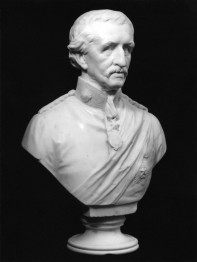

Sir Arthur Cotton had made a career of crossing the line where India was concerned, taking stands that irritated his superiors even as they earned him much local admiration—two districts of Andhra Pradesh hold an estimated 3,000 statues of the man. He was, of course, as much an imperialist as his peers, but it was not a desire to bring glory to Great Britain that motivated him. Instead, this 10th son of the 10th son of a regrettably named Sir Lynch Cotton had experienced a religious awakening as a young man in 1826. Thereafter, he felt his mission was to work “for the glory of God…and the benefit of men”, and with familiar racial condescension, he decided that the men in question were poor brown Indians. His self-righteousness, however, was wedded to sincerity—having taken up the Indian cause, Sir Arthur never gave up, describing himself as “a man with one idea” that could make a difference in India: irrigation.

Sir Arthur was a military engineer who caused his colleagues great consternation by refusing to be awed by steel and steam. He had no dispute with the railways but it made no sense to him that extortionate technology should be imposed on a landscape where the basics had been entirely neglected. But then he was also somewhat naive—he once argued against the term “collector” since it suggested that revenue officials’ sole interest lay in extracting money, when surely they were also responsible for that other thing called development. The architects of the Raj, of course, were under no such delusions—the collector was there precisely to collect, and Sir Arthur’s lifelong mistake lay in hoping that India’s wants would also somehow feature in those exploitative calculations masquerading as government policy. Naturally, he was thwarted by “administrative jealousy”, and many were those who called him a “wild enthusiast” with “water in his head”.

Still, Sir Arthur was tireless. In 1827, after inspecting the second century Kallanai dam near Tanjore, he regretted that “this work, which had a population of perhaps one hundred thousand and a revenue of £40,000 dependant upon it, had not been allowed £500 to keep it in repair.” He personally rode out to persuade his superiors to correct this, only to be rebuffed. “Government,” he was told, “could not squander such sums as this upon the wild demands of an Engineer.” “Is it surprising,” he asked in dismay, that “the natives thought us savages?” Nevertheless, he kept up his interest in irrigation—learning from furloughs in Australia, as well as travels in lands as diverse as Egypt and Syria—till finally he was able to leave a real imprint along the eastern coast of India; something his daughter called “The Redemption of the Godavari District” through, as his brother chuckled, “The Cheap School of Engineering”—also known today by that Indian word, jugaad.

The British, Sir Arthur thought, brought “disgrace to (their own) civilized country” by their “grievous neglect” of India. He decided to make amends. When the Godavari project was sanctioned in 1847, Sir Arthur asked for six engineers, eight juniors and 2,000 masons. Instead, he was allotted one “young hand”, two surveyors, and a few odd men. Yet he persevered. “To save on masonry work,” Jon Wilson writes, “he copied the method of construction” used by the Cholas. “Cotton created a loose pile of mud and stone on the riverbed, which he then covered in lime and plastered with concrete, instead of building up entirely with stone.” The whole project was finished at a third of the cost initially estimated, till 370 miles of canals (339 of which were navigable) irrigated some 364,000 acres of land, transforming a dry expanse into the “rice bowl” of Andhra Pradesh. And waterways, the Englishman demonstrated, were a doubly rewarding alternative to rail transport, simultaneously nourishing the farmlands of rural Indians.

In the end, however, Sir Arthur couldn’t prevail over the railway lobby. Between 1885-87, the railways cost £2.84 million while the irrigation budget stagnated at a measly £6,130. As late as 1898, the year before his death, it was stated that rail absorbed “so large a measure of Government attention, (that) irrigation canals, which are far more protective against famine…are allowed only one-thirteenth of the amount spent on railways each year.” It was easier, Sir Arthur sniffed, to propose a £4 million railway project over a £40,000 irrigation scheme. He had no dearth of ideas, however, offering a pan-India river-linking project, and bombarding his bosses with notes and suggestions till they finally established, almost out of sheer exhaustion, a public works department—the ubiquitous “PWD” of today. And after collecting his shiny knighthood, he continued to cheerfully lambast the Raj for its neglect of India, receiving a more profound honour instead from ordinary peasants, who, to this day, remember Sir Arthur less as a representative of the Raj and more as a local saviour.