(My column in Mint Lounge, July 20 2018)

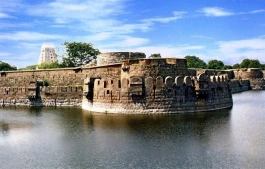

On 17 July 1806, British authorities in colonial Madras rescinded a four-month-old order that had bathed the countryside in a monsoon of blood. A week earlier, soon after the moon rose on the night of 9 July, serving sepoys had mutinied in nearby Vellore. Over a hundred British officers were put to death—the commander, as he emerged in his bedclothes—and the few Westerners who survived did so either by playing dead or hiding in a gatehouse. Even as a lone officer raced to Arcot for reinforcements, the mutineers forgot their principal purpose and succumbed to the attractions of plunder: When the Arcot troops arrived at 8 o’clock, they discovered that the rebels of this so-called first war of independence had forgotten to even lock the gates of the fort they had only hours before triumphantly “taken”.

Retribution was swift—of the 1,500 Indian troops present, about 400 were killed immediately, some of them blown out of cannons, presumably to send the message far and wide. But the British themselves were terrified. Power in India was tenuously held to begin with, and if even their own troops could not be counted on, the Raj was on less than solid foundations. By the time news of the mutiny reached England, months had passed, and the horror of the Madras authorities was matched by dread in London at this “disastrous event”. A commission of enquiry had already been constituted. As one officer later said, “The natives of Hindostan are meek and submissive beyond any other example in national character.” What then caused these spineless men to stand up to the white master? The answer, the officer offered, lay in an old saying: “If you prick them, they will bleed; if you insult them, they will revenge.”

But the provocation was, on the face of it, bewildering—it was a simple matter of uniform. In March that year, the Madras authorities had issued new dress regulations for consistency. Beards were banned, and moustaches standardized. A new turban was designed, with a feather, a leather cockade, and a flat top. Superficially, these were simple innovations, but, as the British discovered, in India costume had much to do with custom, and dress was not merely an issue of dressing up. Appearance signified caste, and in a veritable whirlpool of identities, sartorial conventions were a matter of honour. As the enquiry concluded, “Nothing could appear more trivial to the public interests than the length of the hair on the upper lip of a sepoy.” But to the sepoy himself, “the shape and fashion of the whisker is a badge of his caste, and an article of his religion.”

This ought not to have been a surprise. As soon as the new turban (which was especially resented for resembling European hats) was introduced, soldiers had raised objections. For their pains, they were rewarded with 500-900 lashes. Some sensible commanding officers on the ground knew the risks—in Hyderabad, where rumour already presented Christians as requiring the heads of 100 natives to consecrate churches, the officer in charge refused to execute the dress regulations. In Vellore, however, the orders were firmly enforced. The result was a conspiracy so outlandish in its initial rumblings that even when alerted on multiple occasions, the British pooh-poohed it instead of allaying the concerns that led, at last, to tragedy.

As London put it, 1806 became, then, the first example of “the Native troops rising upon the European, barbarously attacking them when defenceless and asleep, and massacreing (sic) them in cold blood”. Of course, admitting that this bloodbath was due to a misunderstanding about moustaches and turbans felt a little awkward, so a number of other instigations were paraded—there were arrears of pay, so there must have been resentment. Though there were no Christian missions nearby, missionary polemics must surely have provoked the sepoys, it was added. But most important of all, the real conspirators—despite lack of real evidence—were the family of the dead, fearsome ruler of Mysore, Tipu Sultan (reign 1782-99), housed in Vellore fort.

This theory conveniently suited an old British prejudice that the “main instrument of mischief were Mahomedans”—a point that would be made even more forcefully decades down the line, after the sensational events of 1857. Behind the smokescreen of offensive uniform, the Muslim sepoys had wanted, the authorities claimed, to restore Tipu’s line to power. As in 1857, when the rebels would resurrect the emaciated Mughal emperor, in 1806, too, during the few hours Vellore was in their control, the soldiers had named Tipu’s son their leader. The wedding of Tipu’s daughter, Noor-al-Nissa, the previous day had allowed them to set the rebellion in motion behind the general noise and activity. An old flag of the Lion of Mysore (purchased, incidentally, from a Parsi merchant in the local market) was also unfurled that fateful night—all this was construed as “proof” that the Mysore royals were involved in the uprising.

As it happened, the Mysore party might have had a role to play in so far as stoking the fire in 1806 went—attendants in service with the princes had goaded already upset sepoys by calling them unmanly “topiwallas” who sacrificed their honour for firangi coins. The result was a combination of caste and religious pride, political vendetta, and accumulated resentment against British haughtiness, culminating in spectacular slaughter. Just deserts awaited: The Mysore family was packed into 12 ships and exported to Bengal. Punishments were handed out to those mutineers who had not already been chopped to pieces. But even as the facade of control returned, the monsoon of 1806 in Vellore sent the first major jolt to the founders of the Raj that they were not, ultimately, welcome in India—and that what would become the jewel in the empire’s crown came soaked in blood and ferocious anger.